The Israel Trail: Procession

Making of The Israel Trail: Procession

The Israel Trail: Procession – Ayelet Carmi and Meirav Heiman

- The Trail, The Convoy >> Tali Tamir

- Remainders of a Ritual >> Galia Bar Or

The Body Knows

Drorit Gur Arie

The roads have no eyes to see

the depth of their travelers' dreams

Avraham Chalfi1

"The land can be felt by stamping one's foot and by forceful treading; nature can be breathed better from within"2—thus, in the spirit of the Zionist ethos, the shapers of the new Hebrew culture sought to combine the pioneering debka3 steps with the so called Yemenite step; to blend the profound desire to assimilate in the region and the heritage of the immigrants who came from distant lands. The unique fusion of avant-garde and secularism—the connection between the feet conquering the clods of earth through labor and the bare feet dancing in nature—crystallized into folk dancing which was celebrated in festivals in Kibbutz Dalia (1944–68). The Jewish settler (referred to as "pioneer" in Hebrew) will dance the Hora, rather than the East European, ultra-Orthodox Mitzvah tantz4—ideology thus demanded, decreeing that "dancing in Hebrew" means close to the soil, in nature's bosom, and together. Folk dancing and holiday celebrations in the kibbutzim incorporated various artistic fields into a symbolic-mythical narrative, which reflected the political and cultural values that defined Israeli society: pioneering and nationalism, nature and land, ingathering of the exiles, physical strength and labor.

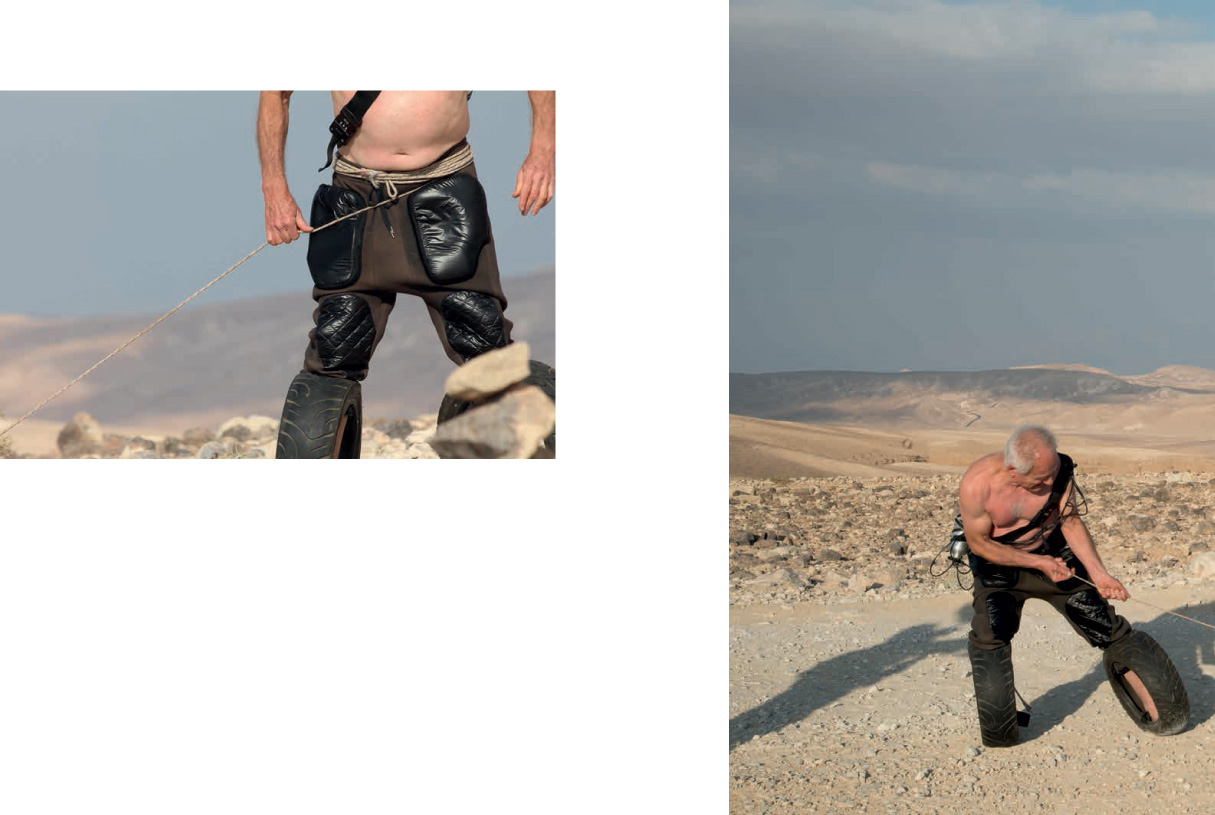

A quick Google search attests to the current popularity of marching songs along the Israel National Trail, which join a long line of hiking and road songs in the national-Zionist context. In Ayelet Carmi and Meirav Heiman's work, the collective journey along this lengthy walking trail echoes the same burning passion to conquer nature with the hikers' feet, as a substitute for climbing the heroic paths of the past, such as climbing up to Masada. Carmi and Heiman's odd, mesmerizing procession unfolds in monumental projections on three walls of Petach Tikva Museum of Art, proceeding as contemporary choreography whose rules have been meticulously outlined. A non-walk walk, it refuses the heroic gesture of "stamping and forceful treading." The journey participants—hikers, nomads, survivors, and refugees—proceed along the route, being carried and held by strange contraptions which prevent contact with the clods of earth. The progression from one point to another, performed without touching the ground, results in an acrobatic, circus-like show—or possibly a dance-performance, since the design of the gender-blurring, tight-fitting leotards and the various accessories (e.g. knee protectors) was drawn from the arena of contemporary dance.

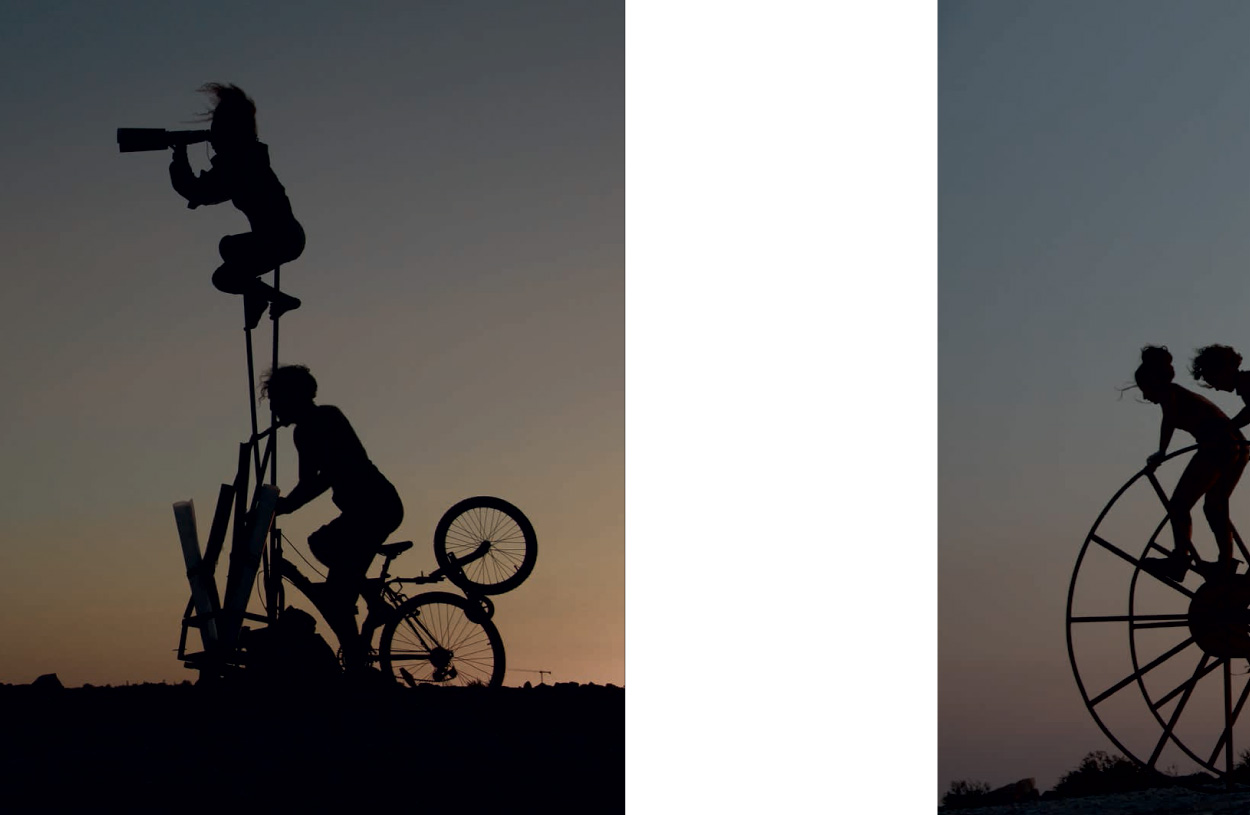

Two young women advance on a drip-irrigation-reel while maintaining balance; one leans forward, while the other stabilizes the device by leaning back with all her weight. Another pair walks on a star-shaped structure, a progression (walking, falling, advancing while rolling along the path) which requires planning and fine coordination between the one inside the star and the one above it. Another group staggers on streetlight globe shades, while yet another family measures steps, stretching a thread, rolling it up, and resuming counting steps in a private ritual of sorts. The procession moves forward in varying rhythms, with the help of apparatuses made of ram's horns, bikes for disabled people, and various types of crutches—beat, stroke, stop, physical effort, and concentration on the body.

Zali Gurevitch and Gideon Aran's formative essay addresses the conceptualization of Zionism around the notion of the people's return to its homeland. Israeliness is often interpreted as localism which is fundamentally antithetical to diasporism; this localism, however, is a longed for destination, an object of yearning, and the root of the problem underlying Israeliness, since "the place has not yet fallen into place." In the Israeli experience, there is no full identity between the Israeli and Israel, and there is aversion to total assimilation in the country. This discourse of identity is underlain by a constant struggle over the place—a struggle that takes place primarily among ourselves, centered on the meaning of the place and our identity as its natives.5 The place—all the more so the Israeli place—is never neutral, "because, from the very outset, it was shaped by opposing parties, wars, battles, occupation, Hebraization. […] Israel is, a-priori, a pedagogical, ideological site of strife linked with a history of conquest and settlement, with a history of 'inscribing,' 'dictating,' and 'rewriting' the place."6 In the religious experience and the experience of archaic sanctity, on the other hand, the place (HaMakom) is a key concept, the infrastructure of the identity binding the individual to the world, and through the world—to himself.

"Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee" (Genesis 12, 1)—God orders Abraham, establishing the Gordian knot between man and land (Heb. adam-adama), and subsequently also blood (dam). The land is the raw material for the primeval creation; at the same time, however, it also signifies the end and the return to its bosom, as the physical departure from and return to it are simultaneously conceptualized as a proof of faith. In this spirit, Leah Goldberg's "End of the Road Songs" recount an internal journey through life's twists and turns, a movement that generates a change of consciousness—an age-old existential state, described by Yehuda Amichai as "walking which is passed down."7

In Carmi and Heiman's The Israel Trail Procession, the aura of the past and the formative experience associated with the local ritual of hiking collapse. What remains is only the body's act, its physicality and performance, in intense, multi-directional activity. Contemplating the "body without organs" (Corps sans Organes) introduced by Deleuze and Guattari after Antonin Artaud, the body allows the powerful multiplicity to flow through it, deterritorializing and deconstructing the organism which is constructed as a logical system of cause and effect, beginning and end. The "body without organs" is a metaphor for the intensity of immanent desire. The organs of desire do not disappear, but their random action does not organize itself into logical sequences. The organs are nothing but currents, potencies produced by desire that operates for its own sake and is focused on itself.8

Carmi and Heiman's procession has no definite markers of place or time. It may be construed as a mythical or timeless procession—a grotesque pilgrimage which crosses space and time, possibly in the distant past, possibly in some perverse futuristic mirage. Flags, symbols, objects, and items of clothing are uniquely processed as ritual memory residues, or as apocalyptic anticipation, or as a combination of the two. The structure does not strive for any particular goal. In fact, it exists in the depths of its inner passion. Is this a procession of martyrs, or—judging by the conspicuous feminine presence of singers, horn (shofar)-blowers, stevedores, flag bearers, and acrobats—a female rite of initiation? The circus-like means of transportation and the jugglers using them call Dominique Jando's thesis to mind, regarding the circus as a site of female emancipation: a place that enabled women's artistic and professional realization without being disrespectful of them in times when female sexuality and athleticism were oppressed by conservative and religious establishments. The externalized physical culture of circus acrobats allowed the externalization of sexuality (by both sexes) in an oppressive cultural climate.9

Carmi and Heiman's female circus performers—women of various ages, whether priestesses or warriors—appear to be suffering and a long way away from liberation due to their attachment to the various aforesaid devices. This is not a procession of self-realization or feminist liberation, but rather a circus of suffering or a protest march which exposes the body's difficulties for all to see, including injuries, bruises, and blisters. Momentarily, we are faced with a procession of pilgrims caught in a religious adventure of self-purification aided by mutilating torture apparatuses; but while the pilgrims of the past embarked on a transcendental experience which deviated from their own being and was rife with physical and mental tests, contemporary pilgrimage a-la Carmi and Heiman has no set destination guiding it. It is a process-minded, multi-focal experience; a nomadic journey whose end is unknown, neither is it important, because its essence is learning and gathering experiences. In Carmi and Heiman's The Israel Trail Procession, the wanderings are for their own sake, and the odd walk spawns a self-governed world, an ongoing Sisyphean act: the thread rolling in the hands of the step surveyors echoes Sisyphus, who rolled the rock up the mountain in vain, while the priestesses' song conjures up the sirens whose singing accompanied Odysseus's journey.

The work's colorful spectacle resembles a dreamy illusion, a pilgrim fantasy which commences with anticipation and promise for a "great pleasure excursion to the Holy Land," and concludes—as did Mark Twain's voyage—with bitter disappointment of the "dismal scenery," where "every outline is harsh."10 Carmi and Heiman's nomads stand on the border—or light—line of Israeli-Zionist existence, behind which a dark world of instincts lurks. Night falls on the procession. The convoy, with its people and devices, goes quiet. Shadows are colored orange and black, and everything transforms into a tableau vivant of pioneers, adults and children, tilling the land, as in Meir Gur Arie's silhouette piece from the Bezalel period. Last day, a beautiful, rueful hour in a silent, all absorbing wilderness.

Research: Bar Goren, Daria Kaufmann, Shira Tabachnik, Or Tshuva, Bar Yerushalmi

Notes

- Avraham Chalfi, Poems (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1986–88) [Hebrew; free translation].

- Ruth Ashkenazi, The Story of Folk Dancing in Kibbutz Dalia (Tel Aviv: Tamar, 1992), p. 22 [Hebrew].

- Debka (dabke) is an Arab folk dance native to the Levant.

- Mitzvah tantz is a Hasidic custom whereby honorable men dance before the bride on her wedding night holding either ends of a handkerchief or a napkin.

- Zali Gurevitch and Gideon Aran, "Al Hamakom (About Place): Israeli Anthropology," in Zali Gurevitch, On Israeli and Jewish Place (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2007), pp. 22–24 [Hebrew].

- Ibid., p. 14. The Hebrew term "Makom" (place) denotes a physical site or a particular geographical location; at the same time, it also refers to the divine, alluding to God's ubiquitous presence (HaMakom).

- Yehuda Amichai, Now and in the Other Days: Poems (Tel Aviv: Likrat, 1955), p. 36 [Hebrew].

- See Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, "November 28, 1947: How Do You Make Yourself a Body without Organs?", A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), pp. 149–166.

- Dominique Jando, "Venuses of the Age: The Female Performer Emancipated," in Noel Daniel (ed.), The Circus, 1870–1950 (Cologne: Taschen, 2008), pp. 198–273.

- Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad: or, The New Pilgrims' Progress (Hartford, CT: American Publishing Company, 1869), chap. LVI, p. 606.