The She-Joker

Tamar Hammer

The She-Joker wants all or nothing. She sticks her neck out. She is the Medusa. Her hair is disheveled like a heap of yellow snakes, and she contorts her face in a terrible smile. It is only her reflection in Perseus’s protective mirror that enables him and us to observe her ghastly face. The reflection — art — sweetens the horror of life for us, making it bearable, and lets us observe ourselves through it.

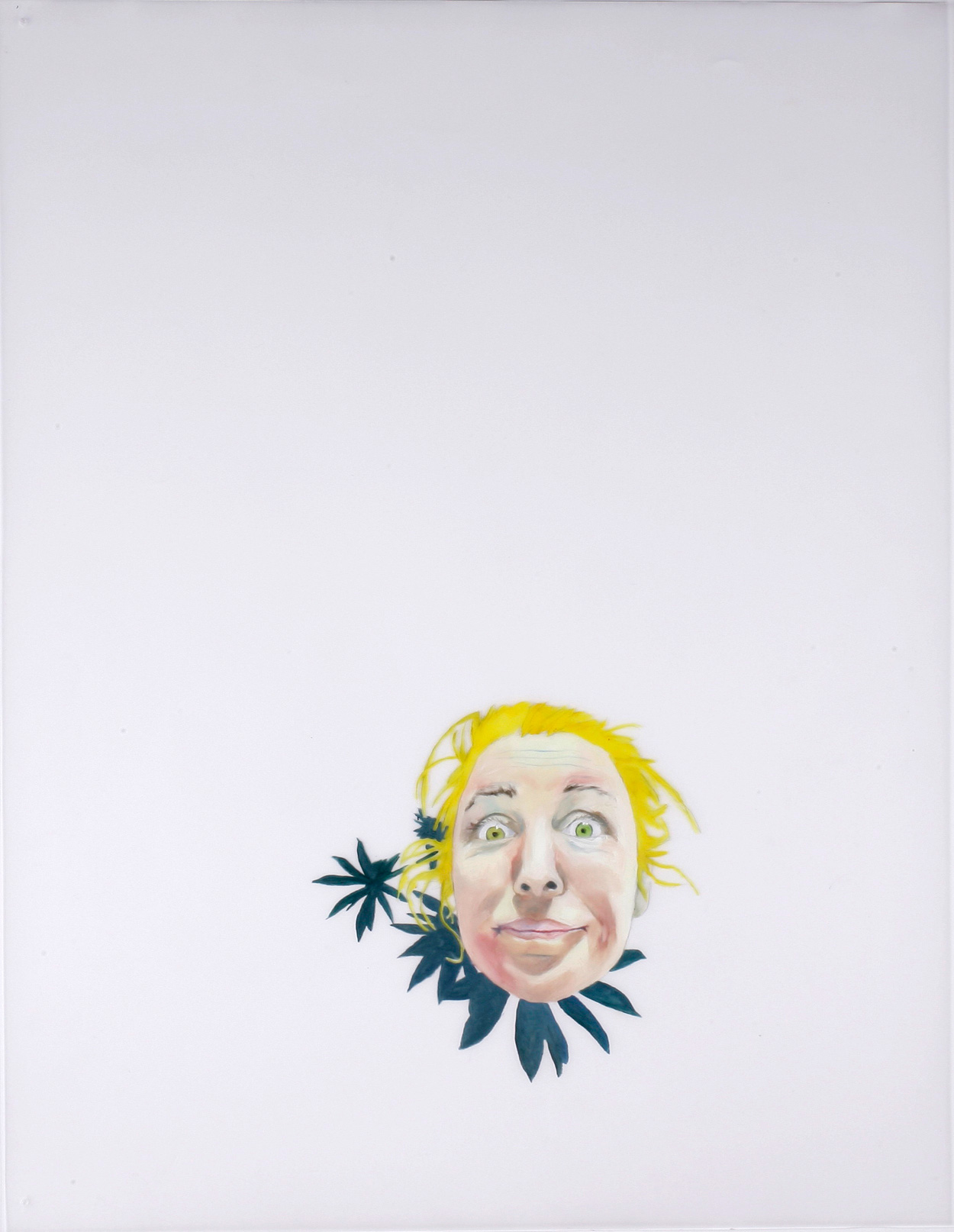

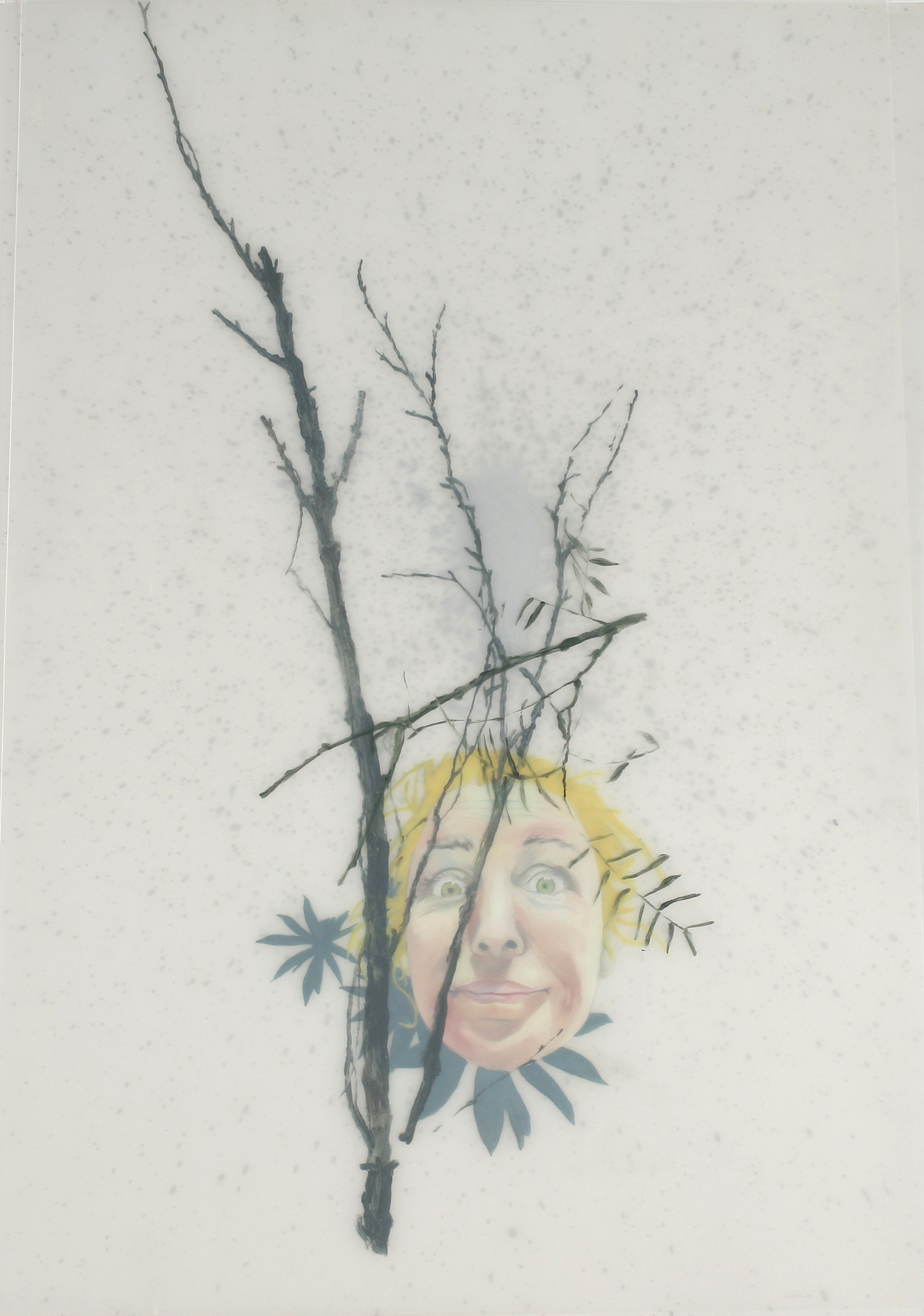

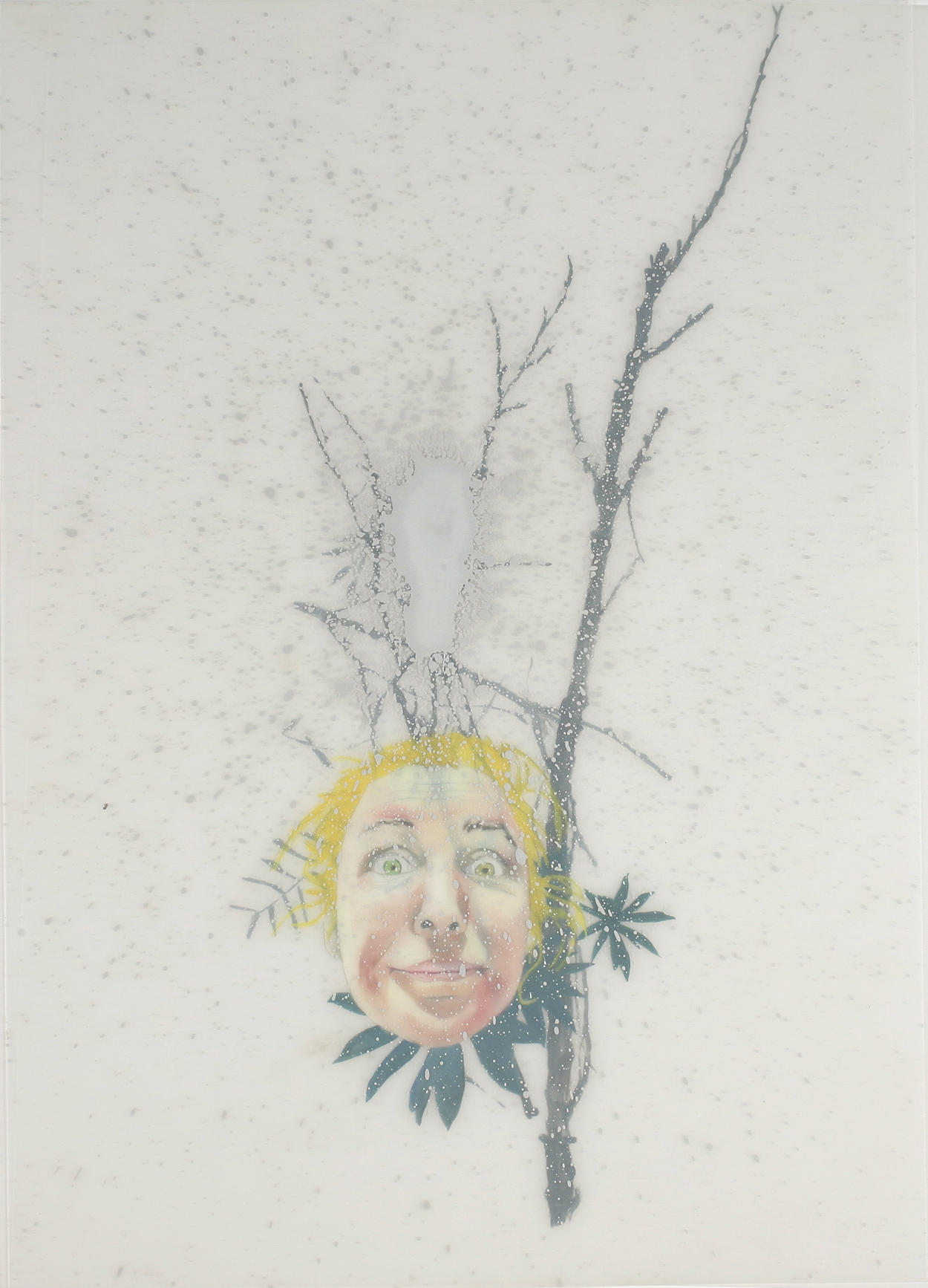

Hence, it is only natural that the series “The She-Joker” is painted on transparent plastic sheets akin to blown-up, double-layered playing cards. The act of reflection and the use of a mirror make the image possible.

The top card — the decapitated head, a self-portrait created from a piercing observation in the mirror; the bottom card — abstract color stains, subconscious Rorschach inkblots combined with branches, residues of nature, and references to her previous journeys. The fusion between the two sheets produces the final image.

Ayelet Carmi’s previous works repeatedly featured a powerful miniature female figure in a fantastic-Sisyphean world. Traversing supernatural realms, confronting predators (lions, tigers, and wolves), carrying their heads with her as trophies, drawing inspiration from the figures of knights with swords and armor, confined within monumental globe-like black spheres, handless in the exhibition “Alexantropia,” where her blood was spattered on the black canvases — an ongoing, detailed description of exhausting journeys, battles, and training.

In “The She-Joker,” the female image is painted from self-observation (self-portrait), rather than from observation of the other (the female model). It is a self-hunting — the artist capturing her own reflection and cutting off her own head in recognizing herself as Medusa, with a crooked smile — ”I am the painted monster” — as the filter softening the horror of life; a Medusa whose reflection in the mirror of the knight’s shield has become a trap, the irony of fate.

Subsequent to her unique protest in the exhibition “The Maccabiah” — through the use of Israel’s flag, its representation as dwarfing and hiding (decapitating) the fighter’s head in her journey, and the collapse of the flag as a concept — Carmi reinstates the lost head, replacing it with her own head, shifting from the Maccabiah games to the global game of cards.

Both types of play — the flag’s hoisting and the pulling of a joker during a card game — are underlain by a sweeping dramatic assumption of an imaginary glory of victory kindled in the air.

The strategy is sharply radicalized in “The She-Joker”; a freezing doubling, as in a mirror, of the omnipotent “winning card”; the megalomaniac card which dooms victory and scorn of the other. Protest vis-à-vis the capitalistic, occupying, phallic status-quo. It is a disconcerting self-portrait which leaves the viewer feeling perplexed. In the totality of Carmi’s oeuvre, it is yet another step in her defiance of the intolerable in our existential reality; an exaggerated manifestation of the ridicule and female cry of a fighter who chooses to look in the mirror.